That Bell No Longer Tolls: Faulty Memory Japan, Part Three

In which our hero thinks he learned about parking garages and saw where the world ended.

For people of a certain age, who grew up in a certain part of the world, the specter of nuclear war always loomed large. In small-town Canada in the 1980s, at least, this was understood as fact.

My parents were born a few years after the end of the Second World War, and spent their youths in public schools where nuclear bomb drills were, they claimed, common. Like my generation knowing “don’t drink and drive” and “stranger danger” and “only you can prevent forest fires” by rote, my parents grew up with “duck and cover,” which is frankly awful advice for avoiding a nuclear Armageddon. My father—for whom it was a virtue to prove that his life had been more difficult than ours, than anyone’s—missed few opportunities to remind us of how easy we had it, how a fire drill was nothing really compared to the whirr of the air raid siren, the throwing yourself to the ground, the crawling under your ridiculous school desk for safety, the burying your head between your knees and hoping this wasn’t the real one. He also had a penchant for getting his kids Christmas presents from the dump and screaming at his wife all night, so six of one, grain of salt etc.

Still, North American baby boomers grew up in a world in which mutually assured destruction was a monthly—if not daily—worry. Pop culture obsessed about the bomb for decades. Dr. Strangelove, The Day After, these were but the merest satirizations and fictionalizations, an easy mental leap from the oft-repeated promise and terror of the arms race. Growing up in the total calm of deep backwoods Ontario, I struggled to understand the concept of destruction on a large scale. I assumed the bombs would just kind of … miss? Our town had nothing of interest even to its residents, so the idea that it could be a strategic target was laughable. That our tiny farm, a million miles from a pointless town a million miles from the nearest city, would be on any radar was absurd. There was nothing to be afraid of and what the hell was a nuclear bomb anyway?

And then I learned about Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

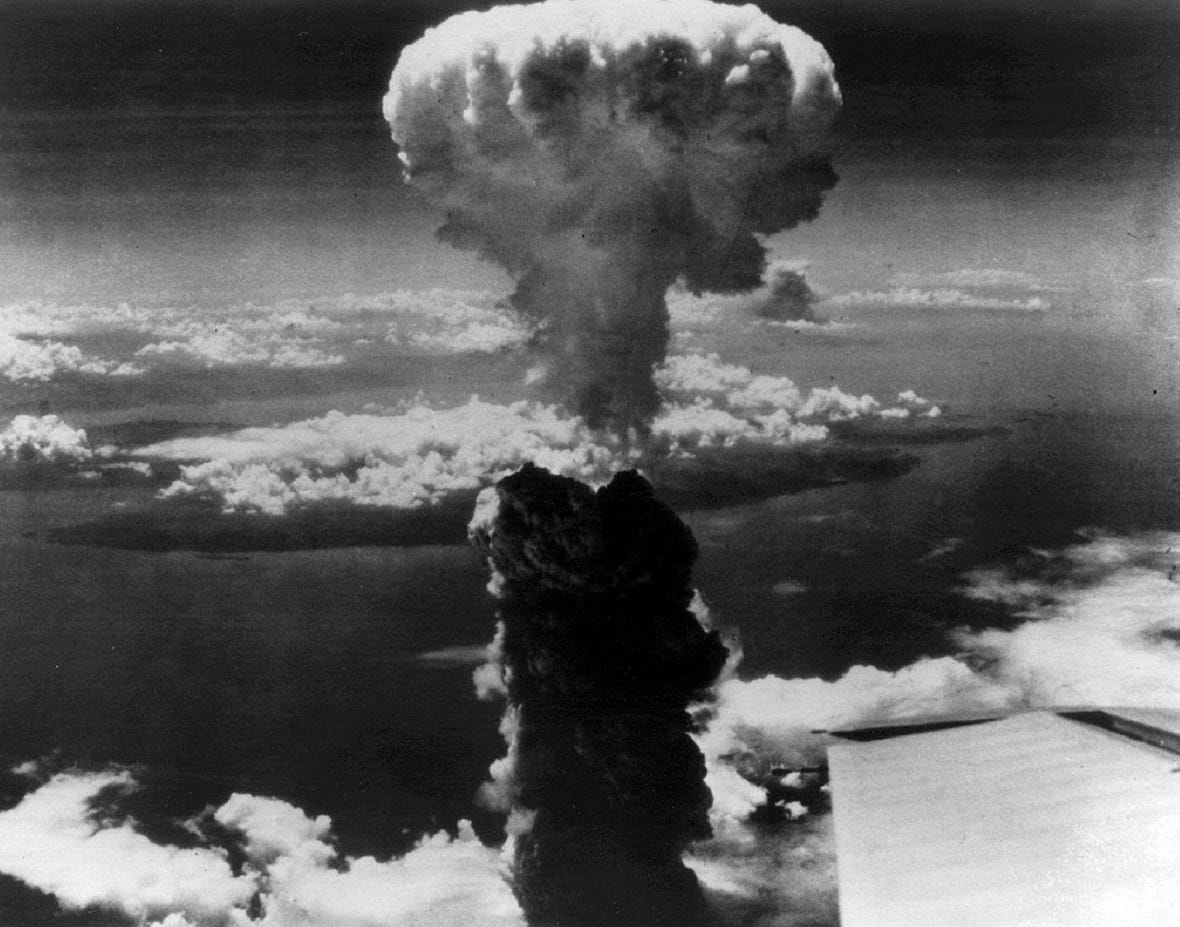

The story of the bombs that were dropped in 1945 requires no retelling here, because we all know it off by heart: world-ending, era-busting, paradigm-shifting, unspeakable, very-much-speakable, all that. It was told to me a thousand times or more, varyingly specific or vague, but all tellings leaving a single lasting impression of the complete destruction of two small Japanese cities.

So when I visited Nagasaki, I was confused by its being so very alive. Japanese cities can be drab, a consequence of 1950s reconstruction efforts (let’s not forget that before the nuclear bombs, the US effectively destroyed most Japanese cities with heinous firebombing campaigns; everything wooden was burned, and Kyoto and its citizens were spared only by a passing fancy that General McArthur had been stuck by the city’s beauty during peacetime). Many of those firebombed places are grey and concrete and on perfect grid plans and alive in a perfunctory sort of way, people going about their lives—sometimes with eagerness but usually, from the outside view, with a kind of duty to complete a checklist; the enthusiasm of a talented accountant or a mediocre musician.

It’s an obvious and slightly stupid thing to say that Nagasaki felt so alive because I associated it with death. It’s also a true thing, which is inconvenient. When Erin mentioned that she wanted to do a day trip to Nagasaki, a strange dry lump formed in my throat. It was part fear, part daftness. I didn’t want to be radiated and I didn’t know how solemn I was supposed to act. At the time, I had never been to any place with serious radiation (Nagasaki doesn’t have this) nor anywhere that was historically and/or culturally significant because of a mass murder, so I forgive younger me for that initial reaction. I’m not bragging when I say I am more familiar with those situations now, nor proud when I say I still have no idea how you’re meant to behave in them.

But about that first time:

Nagasaki sits in this lush little armpit in the southwestern corner of Kyushu (the world’s 37th-largest island, don’t forget). I’ve neglected to mention how green Kyushu is, all volcanic soil and rainforest and mist hanging low in the winter mornings. I take this somewhat for granted now, having visited jungles and frowned at all their awful bugs. But this was a first-in-the-world-temperate-climate-that-is-green-all-year sort of place, and I’m sure I spent the morning drive saying “Look at how green that is!” and “It’s so misty!” until Erin turned up the music.

We approached Nagasaki from the east, on winding roads that offered only glimpses of the seaside city. That low hanging mist made progress slow but pleasant. There’s something about the way a drive that fights the weather heightens the expectation of the destination, adding a sense of reward to a pre-made plan. We’d left early in the morning, possibly in the dark. It felt early. The occasional glances at a fabled place were tantalizing. Finally in Japan I would see a place I had heard of, 36 hours in Tokyo notwithstanding. This was probably what travel was supposed to be about, right?

We must have parked the car somewhere outside of the centre, and I have a faint memory of Erin wanting to show off the ingenuity of the Japanese by parking in one of the country’s bewildering vertical parking lots. You drive your tiny car onto a tiny metal circle that sits in a hole in the wall, you punch some buttons on a control panel or you ask a man in a uniform to do this for you, and then the circle spins and your car disappears upward into a building to be stored, kind of like a reverse vending machine. I know these places exist in Japan. I cannot say with any degree of certainty if we used one that day. Either way, we walked and did not drive around Nagasaki.

I remember long, covered streets and steaming piles of food. I remember it rained for a while, and the reason for the covered streets became obvious. I remember trying takoyaki, little dough balls stuffed with chopped up octopus and covered in mayonnaise and barbeque sauce and fish flakes. We walked, we ate, we stopped at an arcade and played Mario Kart—the kind where you sit in a car with real pedals and a steering wheel and yell like children. I won handily. We played some kind of arcade game that was like Dance Dance Revolution but for traditional Japanese drumming. Erin won handily. We probably bought a beer from a vending machine and revelled in the freedom to drink it while walking around. Eventually, we headed to the Peace Park.

Careful readers will have noted by now that this Faulty Memory entry is so far low on memory and high on fault. The whole point of the series that I invented is that I can forget stuff or make things up and hide conveniently behind the conceit of “faulty memory,” but the truth of it is I remember quite a lot of this Japan trip, as though it happened last week. The reason I can’t summon the minutia of that morning in Nagasaki with the same crystal clarity as the rest of the trip is that the afternoon in Nagasaki imprinted itself so firmly on my mind that the things around the edges have been completely blown away.

A little outside of the center of the city, a tram silently glides up the slight hill toward what appears to be an average park: trees, benches, some buildings in the middle. The tram’s automated speaker system announces the stop for the Peace Park, and we step out into a warm and sunny street. I forget, as always, that Japan is left-hand drive, and look the wrong way before stepping off the tram. A cyclist swerves around me, looking annoyed but too polite to do anything but nod apologetically. I nod back and mumble a perfunctory sumimasen, looking around to take in the busy street.

Blandly or enthusiastically, people were going about their lives—business people walking down the street with hands full of restaurant take-out packages, or teenagers cutting class to smoke cheeky cigarettes in little alleyways, or the postman in his perfectly pressed uniform hurrying along. It didn’t exactly hum, but there was a kind of low-level persistent background noise to the street that would later strike me as an act of profound defiance.

Approaching the entrance to the Peace Park—though there are many entrances; it’s a circular park without gates—I noticed that the ground changed. Gone were the smooth, ruthlessly clean sidewalks. Surrounding the entire park was a kind of wave of cement, rising parabolically up from the street about 12 inches in a smooth, convex curved line. The effect was that all visitors are asked to make a deliberate step up into the park, minor but notable. Viewed from any point along the circular edge, the effect was sudden and terrifying: this whole memorial was raised up on plinth designed to look like the base of a mushroom cloud, only sliced off in a huge flat circle at an early point in the explosive metaphor, just a foot off the ground. The start, then the immediate end. The bloom, then nothing.

I walked deeper into the park, towards the centre, where some kind of pointy buildings stood in a small, open area. The ground was mostly dirt, strange for Japan with its ubiquitous paved urban outdoor spaces. There were stone monuments and statues and what looked like fountains scattered here and there, but my eyes were drawn to the buildings and I ignored these for now. As I drew closer to the buildings, their form became clearer. They appeared to be two pillars, one black and one red, roughly the same height. The black pillar was of that deep, impenetrable shade that war memorials favour, which made sense, this being one such memorial. The red pillar was made of hundred-year old bricks. It was a piece of church.

Okay, it’s actually a corner of a cathedral. As I got closer, I could see that the red pillar stood on the edge of a series of concentric circles that had been laid into the ground, and that the black memorial stood in their centre on another raised plinth shaped like the base of a mushroom cloud. This, I realized with an instantaneous heart-sinking desperation, was ground zero.

The monument stood perfectly level with the top of the remaining corner of what I later learned had been the Urakami Cathedral, a Catholic church built in 1895. The Urakami Valley had been home to some munitions factories and other heavy industry, which in the twisted logic of the Second World War made it a viable target. Reports vary of the destruction, of course, but it’s generally understood that of the thousands (and maybe more than 100,000) deaths on August 9, 1945, only 150 were military service-people, and that includes a handful of allied prisoners of war. The rest were civilians.

Urakami Cathedral was, of course, almost completely obliterated. There are photos online of the remains of the church in the days following the bomb: only small sections of two walls standing, joined at the corner that remains in the Peace Park to this day. The huge steeple lay toppled, collapsed inward. The photos look fake to me, partly because the current site is so pristine and partly because the destruction is surreal. After the cleanup—how many months or years must that have taken, in the long shadow of the thousands of deaths—all that remained was this stubborn corner, a sad bit of an archway reaching skyward to nothing.

Earlier I talked about not knowing how to behave in such places, in the face of the such destruction. The truth is, you don’t need much prompting. The weight of the situation takes over and you become subdued, solemn, introspective. You act slowly, deliberately. You say little. When thoughtfully and tastefully designed, a memorial has that power over you. Your only responsibility is to allow it.

Moving very slowly, I began to step away from the church and took in the rest of the park. I became gradually aware of two important features of the Peace Park. It was utterly silent, and it was covered in paper birds.

The absence of sound is a difficult thing to notice. You can’t be immediately certain if a moment is simply quiet or if something is missing. No one else was in the center of the park, and neither Erin nor I were speaking or making much noise. But it felt like the place, the specific spot, was devoid of sound. I’m not sure if it felt this way because this little clearing was far from the street, or if it was designed to be shielded from the bustling neighbourhood sounds by well-positioned hedges and strategic stands of trees. Or if it was something more permanent, as though all life on this specific spot had been scrubbed from the earth for eternity, told never to return. Or if I was assuming this last thing, and had sort of blocked out any noise to match that expectation. Who knows? Listen, it was really quiet.

A less difficult thing to notice is a million tiny paper cranes, yet I didn’t see these for the longest time. It wasn’t until I stepped up toward the black pillar that I noticed a splash of colour along its base. There was a pinkish—maybe a heavily faded red—line running along the memorial. I walked around the side a bit to be able to see more, and the reddy-pink turned kind of orange, then yellow. Coming closer, I realized that what looked like a line was in fact a string of origami cranes. And then I realized that there wasn’t just one string, there were dozens, all laid around the base of the memorial like flowers on a grave. And then I realized that there were dozens of dozens of strings, laid not just on the memorial but on any surface with enough space for dozens of strings of colourful origami cranes. The cement flower boxes: full of paper cranes. The weird little statue gardens: full of paper cranes. Everywhere. You get it.

Erin was—if not exactly unmoved or unimpressed by this—aware that it was a thing that happens in Japan. Every year around this time (New Year), students in every elementary school in the country set about making crane wreaths to sent to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There are millions of them. It’s not unusual for the children of a nation to spend a day at school making a thing out of paper as a commemoration. Older Canadians have all traced our hands on different colours of construction paper, cut out those hand shapes with safety scissors, and used glue sticks to make a monstrous turkey-shaped object to take home to our unimpressed parents around Thanksgiving. I have it on good authority that this still occurs in France. Savages!

But this was something different, something that required an uncomfortable amount of thought and emotional processing. Rather than red-brown-orange-yellow turkeys, all of Japan’s schoolchildren had delicately folded origami to very specifically not take home. Think of how this must have come to pass: a teacher in formal clothing and not-entirely-sensible shoes explained to a gang of kids how to patiently fold and refold edges until a form began to take shape. Then the cranes must have been collected and painstakingly threaded onto a long string. Then packed up and shipped across the country to only two locations. Then someone—local schoolchildren, reportedly—brought them here and placed them on every available surface. This was national mourning in paper format, a collective plea to not forget those unspeakable days in the summer of 1945.’

The cranes were utterly haunting, more than the blown-up church or the deeply dark memorial, more than the mushroom cloud shape of everything. I don’t know how long I stood there, hit by the weight of it all. I don’t remember at which point we went to see some giant, vaguely brutalist blue statue of a disrobed Greek philosopher or something that punctured the mood. At some point we got back on the tram, got the car back from the vending machine, and headed back to Kunimi. On the heated floor that night, I dreamt of paper birds and fallen church bells and distant screaming.

The next day, Erin drove me to Fukuoka to catch the high-speed hydrofoil ferry to Busan, Korea. I left Japan completely addicted to the feeling of getting comfortably lost somewhere new, to being confused and happy in equal parts, to hearing sounds and smelling smells that I hadn’t known existed, to laughing with a stranger to diffuse the awkwardness of a language barrier, to being here, wherever here was.

***

Read about Tokyo in part one of Faulty Memory Japan: Adrift in the World’s Largest City.

Read about Kyushu in part two of Faulty Memory Japan: Graveyards and Heated Floors.

It made me think that appreciation comes from knowing the efforts. You could have overlooked the cranes, instead you found the beauty in putting together something that takes some much effort and somehow yet it looked a given the ones who did not take the time to think about. They may have just seen it beautiful.